Competitor Keyword Bidding On Trial

How much is your brand worth? When it comes to Google Ads, it’s not necessarily your question to answer. In fact, your main competitor could be setting the price. Here’s how.

Google Ads allows advertisers to bid on specific keywords. When a Google user conducts a search using that keyword, Google rewards the advertisers with the highest bids by prominently placing their ads in the top 3-5 positions on the search results page. This creates an extremely competitive environment, where competitors often go head to head to earn attention, clicks, and sales from their common audience.

In that environment, it’s not a foregone conclusion that your company’s ads will appear on searches using your specific brand. That means you must bid on your brand terms, including business name, product names, and any others that drive potential customers to your site or products.

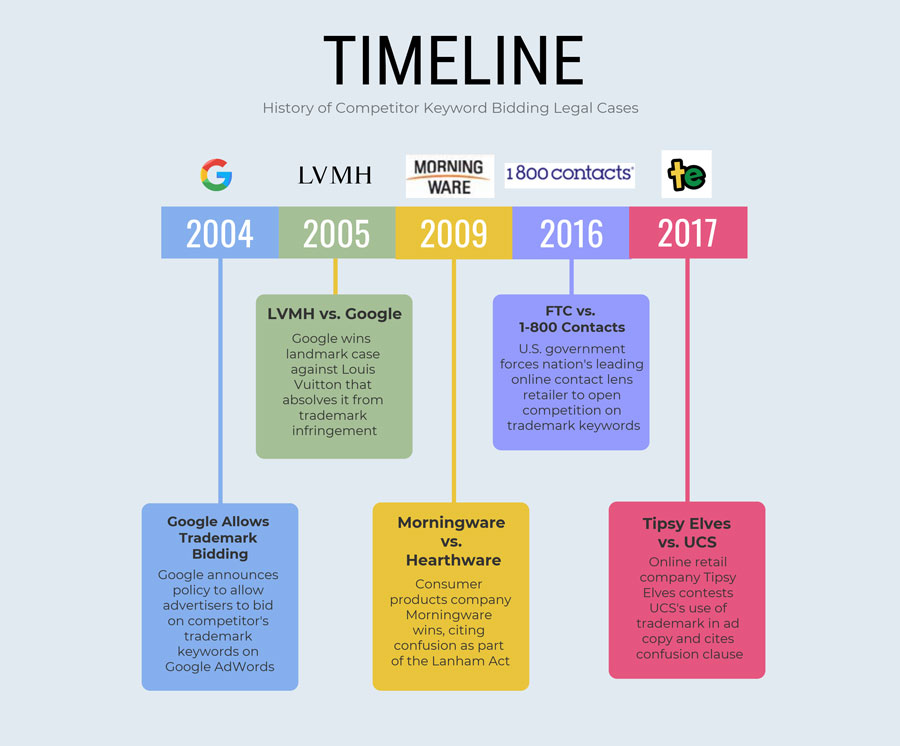

Competing companies commonly bid on the same keywords related to general products and services — an accepted part of online advertising. But companies also bid on their competitors’ brand terms, even if these terms are legally trademarked. In this post we’ll refer to this practice as competitor keyword bidding, a practice that’s come under scrutiny since Google started allowing it in 2004.

In Part 1 of our 3-part series on brand search strategy, we’ll look at a few legal cases that have shaped the discussion around the need to often bid on your own brand, how competitor keyword bidding is affecting the digital media landscape, and what challenges you could encounter when developing your own strategy in 2020.

LVMH vs. Google

In 2003 LVMH, commonly known as Louis Vuitton, discovered that Google searches using LVMH’s trademark terms returned ads for sites selling imitations of LVMH products. This sparked a long legal battle between LVMH and Google that started in 2005 with a French court determining that Google was guilty of trademark infringement.

The decision by the Regional Court of Paris was a potential blow to Google, which was expanding its decision in 2004 to allow competitor keyword bidding in the U.S. Google appealed the Regional Court of Paris decision to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). In 2010, the CJEU ruled in favor of Google, absolving them of any liability because Google was not considered to have an active role in the matter.

This decision also reversed an earlier opinion that prevented advertisers from suing each other for bidding on trademarked terms.

Analysis: This was among the first high-profile cases against Google, and the initial decision looked to be a major obstacle to the profitability of Google Ads (formerly known as Google AdWords). Had the decision carried into the U.S., we’d be experiencing a much different paid search environment than what we have today.

But instead, the CJEU decision not only established protection for Google from future trademark infringement cases, but also established that these matters should be handled between competing advertisers.

Morningware, Inc. vs. Hearthware Home Products

In 2009, consumer products corporation Morningware filed a complaint against its top competitor, Hearthware. The complaint centered around a Hearthware Google ad that returned on searches for the keyword “Morningware”, a trademark of Morningware, Inc. The ad read, “The Real NuWave Oven Pro Why Buy an Imitation? 90 Day Gty”.

The complaint alleged that Hearthware’s use of the trademark was illegal because the prominent placement of the ad on Google, in combination with the “Why Buy an Imitation?” ad copy, demonstrated a false claim of product superiority. This false claim misled or confused consumers into believing Morningware products were “fakes of Hearthware’s products”, according to Morningware’s complaint.

The complaint goes on to say that Hearthware’s ad was intended to mislead or confuse consumers “into falsely believing that Morningware sponsors Hearthware’s own website and potential customers have visited Hearthware’s website after entering the search term “Morningware believing that Morningware…ovens are available from Hearthware.”

In November 2009, the court ruled in favor of Morningware, denying Hearthware’s motion to dismiss. The court cited “initial interest confusion” and “product disparagement” as reasons for the decision. These factors satisfy requirements for protection under the Lanham Act, the primary trademark law used by the federal government.

Analysis: The LVMH/Google legal proceedings were in their fourth year at this point, and businesses were getting a preview of what might happen if they contested Google in court instead of contesting their competition.

That case, combined with Google’s policy to allow competitor keyword bidding, led to an increase in litigation between business rivals, including Morningware vs. Hearthware. Google’s policy also perhaps emboldened businesses to more aggressively target trademarks in their Google Ads strategy.

The Morningware/Hearthware case reinforced a few trends being established around these keyword battles. First, that it was possible for plaintiffs to win such cases in the face of Google’s policy. If companies couldn’t beat Google, they could provide a sound case against their competition, thus, limiting or eliminating their competition’s ability to bid on trademark terms.

Second, that businesses that are bidding on competitor trademarks must stay within legal boundaries, most notably the Lanham Act. Google’s policy also specifies that an advertiser can’t use the trademark in ad copy or the site URL.

So while many cases were being ruled in favor of companies using competitor brand bidding strategies, the Google Ads environment hadn’t become a free-for-all, where trademark law was no longer considered.

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) vs. 1-800 Contacts

In 2004, contact lens retailer 1-800 Contacts began threatening to sue competitors for trademark infringement on search engines. These threats, made over 9 years to 15 competitors, resulted in agreements from 14 of the competitors to no longer bid on 1-800 Contacts’ trademarked keywords.

In 2016, the FTC filed an administrative complaint against 1-800 Contacts, alleging that the agreements:

- Prevented online contact lens retailers from bidding for search engine result ads that would inform consumers that identical products are available at lower prices

- Artificially reduced the prices that 1-800 Contacts pays for Google Ads

- Reduced quality of search engine results delivered to consumers[1]

This complaint was upheld in October 2017 with Chief Administrative Law Judge D. Michael Chappell ruling that the FTC had proved that 1-800 Contacts “unlawfully orchestrated a web of anticompetitive agreements with rival online contact lens sellers.”[2]

Analysis: The results of this case further supported Google’s 2004 policy that encouraged competition on bidding for trademark keywords. 1-800 Contacts, the largest online contact lens retailer in the U.S., understood that many of their competitors would rather settle than incur the costs of a legal battle. 1-800 Contacts then used that leverage to limit competition, a no-no in the eyes of the U.S. government.

Tipsy Elves, LLC vs. Ugly Christmas Sweater, Inc.

In May 2017, online retailer Tipsy Elves, LLC filed a complaint in the Southern District of California against its competitor Ugly Christmas Sweater, Inc. (UCS), alleging trademark infringement, among other violations.

The complaint stemmed from an ad purchased through Google Ads by UCS in 2016. The UCS ad used Tipsy Elves trademark in its ad copy, a clear violation of Google policy. Tipsy Elves argued that the use of the trademark term, which appeared over the UCS link was likely to confuse, mislead, or deceive consumers — a violation of the Lanham Act. Just more than a month later, the two sides settled.

Analysis: This appears to be a clear case of trademark infringement, which is most likely why it was settled in short order. Not only did UCS violate Google policy, but more egregiously, it violated the consumer confusion clause of the Lanham Act.

This case was important because it solidified a legal trend in similar trademark infringement cases. If plaintiffs could prove consumer confusion, they could win in court or come to a favorable settlement with their competitors. As more decisions come down to this specific clause within the Lanham Act, the rules and risks become clearer for advertisers.

This also was one of the few suits that left Google out of the equation entirely. With more than 50 wins under its belt in similar cases, Google has precedent, and nearly unlimited resources, to protect itself from trademark infringement lawsuits.

With clearer rules and Google’s protection, we’re likely to see more cases like Tipsy Elves and UCS, where competitors contest one another directly and settle quickly.

Conclusion

Not only is it Google policy to allow competitors to bid on trademark keywords, but legal trends tend to favor the companies bidding on their competitor’s trademark keywords. With this in mind, there are few key things to note when analyzing how your competition is advertising their own products and services on Google:

Monitor your trademark keywords. Your competition is likely bidding on your trademark keywords, but Google policy restricts them from using your trademarks in ad copy or site URLs. And the Lanham Act restricts them from using your trademarks in a manner likely to cause consumer confusion. As these guidelines solidify, you can more accurately assess when your competitor’s strategy becomes illegal and take appropriate action.

Don’t expect a lot from Google. Google has won major legal battles on this issue, and it would prefer to stay out of them going forward, stating on a support page: “We take allegations of trademark infringement very seriously and, as a courtesy, we investigate valid trademark complaints submitted by trademark owners or their authorized agents. However, Google is not in a position to mediate third party disputes, and we encourage trademark owners to resolve their disputes directly with advertisers.”

Know and follow the rules. Competitor keyword bidding is a well-established strategy for businesses across the world, but it remains a sensitive issue. If your business decides to step into the arena, be sure that you’re adhering to the official policy of the search engine, Google or otherwise, as well as all trademark law.

As you can see, competitor keyword bidding is a complicated issue with serious legal and financial ramifications. From protecting your own trademark terms to bidding on your rival’s, it requires a professional attention to detail and constant monitoring.

In Part 2, we’ll examine how these legal precedents affect your brand search strategy, including an in-depth look at whether not bidding on brand terms is a viable option in 2020.

[1] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2018/11/ftc-commissioners-find-1-800-contacts-unlawfully-harmed

[2] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/10/administrative-law-judge-upholds-ftcs-complaint-1-800-contacts

Stay In Touch.

Subscribe to our monthly email newsletter.